REPORTS

Management of Diabetes in HIV: Special Considerations

Presented by:Todd T. Brown, MD

Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, & Metabolism

John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD; USA

In 2002, an article by Schambelan et al. focused on the medical management of metabolic complications associated with antiretroviral therapy (ART) in case of HIV-1 infection.1 Those recommendations were later adopted by the Infectious Disease Society of America as well as the American Diabetes Association. The recommendations provided guidance regarding diabetes screening and management. According to the recommendations, all HIV-infected people should be screened prior to ART, within 4 to 6 months of ART initiation, and every 6 to 12 months thereafter.1

The four main tests used for screening include fasting plasma glucose level, 2-hour plasma glucose after oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), HbA1c, and random plasma glucose levels with hyperglycemic symptoms. When looking at HIV+ patients with body fat changes compared to matched HIV- controls, fasting glucose levels were nearly identical between groups. However, when reviewing the 2-hour post-load glucose results, HIV+ patients demonstrated an impaired glucose tolerance with ~7% having diabetes, as diagnosed by OGTT, even though fasting glucose levels were within the normal range.2 These data suggest HIV+ patients can develop a glucose tolerance issue. There also appears to be a discordance between HbA1c and glucose levels with HbA1c levels being underestimated in patients with HIV+ status, with underestimations increasing with increased glucose levels.3,4 Factors associated with a >0.5% discordance between observed and expected HbA1c include4:

- <200 CD4 counts (cells/mm3)

- Mean cell volume (MCV) (the greater the MCV, the greater the discordance)

- ART use

- Protease inhibitors

- Azidothymidine (AZT).

Diabetes diagnosis in HIV+ people

- Fasting plasma glucose prior to ART initiation

- 1 year after ART initiation

- Consider OGTT in patients with impaired glucose tolerance

ART, antiretroviral therapy. OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

Body fat changes are often seen in HIV+ patients and may include central lipohypertrophy and peripheral lipoatrophy. These body fat changes ultimately affect insulin sensitivity. Visceral adipose tissue (VAT) in patients with central lipohypertrophy, when compared to non-infected controls, is highly predictive of whole body glucose disposal (r2 = 0.94, p = 0.0001).5 HIV+ patients with limb fat loss showed a twofold reduction in insulin sensitivity correlated to the percentage of limb fat (r = 0.60; p = 0.001).6

In addition, the type of ART used may play a role even after medication is stopped. In HIV+ patients on previous thymidine analog ART, subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) was consistently lower than HIV- counterparts, suggesting a possible legacy effect.7 When using modern ART such as darunavir-ritonavir (DRV/r), raltegravir (RAL), or tenofovir-emtricitabine (TDF/DTC), no differences were observed among lean mass and regional fat found with RAL compared with the other two treatments.8 However, there were significant changes from baseline for all groups in trunk fat and VAT fat. Both measures reflect changes in central fat depot and possibly a return to a healthier state. However, this weight gain may come at a cost. In a study of more than 7,000 patients, the amount of weight gained was associated with a greater risk of diabetes compared to healthy controls.9 For each 5 pounds (2.3 kg) gained, patient with HIV had a 14% increased risk of diabetes development compared to 8% for uninfected healthy controls.9 Lastly, switching an HIV+ patient from an older regimen to an integrase inhibitor led to an average 3 kg weight gain after 18 months compared to HIV+ patients on older regimens (efavirenz/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine).10

Glucose management in people infected with HIV is not different than management in patients without HIV infection. Metformin continues to be the first-line therapy. Preliminary studies have demonstrated that the use of metformin may improve lipohypertrophy and coronary plaque in people infected with HIV.11,12 Metformin may also cause a modest reduction in limb fat but this should not preclude the use of the drug.13

It is important to consider drug interactions in patients infected with HIV. For example, dolutegravir, when used in combination with metformin, significantly increases metformin plasma exposure requiring dose adjustments.14 Results using thiazolidinedione in patients with HIV-related lipoatrophy had mixed results for increasing limb fat mass. Pioglitazone demonstrated statistically significant benefits over placebo, while rosiglitazone did not appear to have any effect.15 In addition, there are safety concerns with the use of thiazolidinediones especially in the HIV-infected population, as these patients are more prone to fractures and have a higher risk of heart failure.16,17 Unfortunately, there is limited to no data available reviewing the use of ART with DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1RAs, and SGLT2 inhibitors.

- Consider a lower HbA1c goal because of the underestimation of glycemia

- Especially in patients with CD4 <500 and/or MCV >100

MCV, mean cell volume.

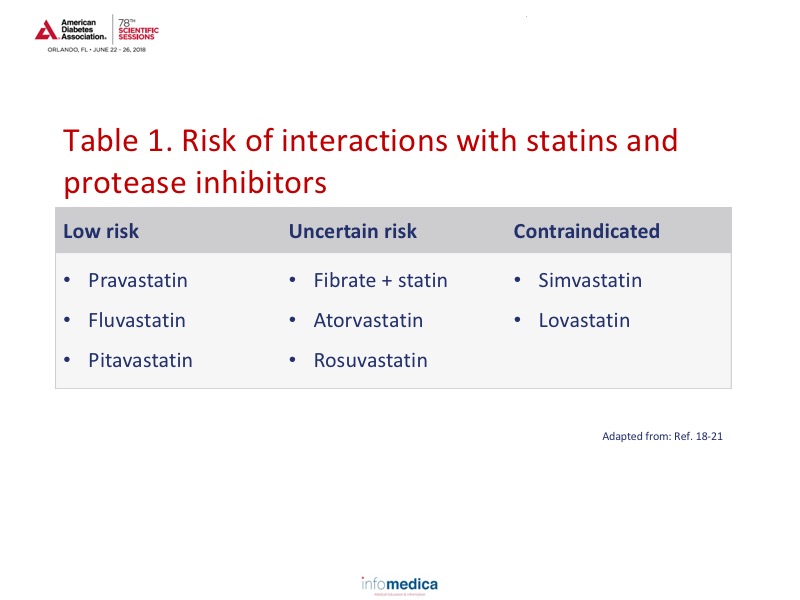

Similar to non-infected HIV individuals, the approach to preventing and managing diabetes-related complications focuses on a multipronged approach incorporating anti-platelet therapy, blood pressure control, cholesterol control, diabetes/glucose management, and smoking cessation. Statin use should be incorporated carefully as there are differences among the statin intensity and interaction with protease inhibitors.18-21 (See Table 1 for the risk of interactions with statin use). For optimal management, patients should be started on the lowest statin dose and titrated upwards. When using atorvastatin with the maximum dose of a protease inhibitor (or cobicistat) the dosage should be 20 mg/day, or 10 mg/day if using rosuvastatin.

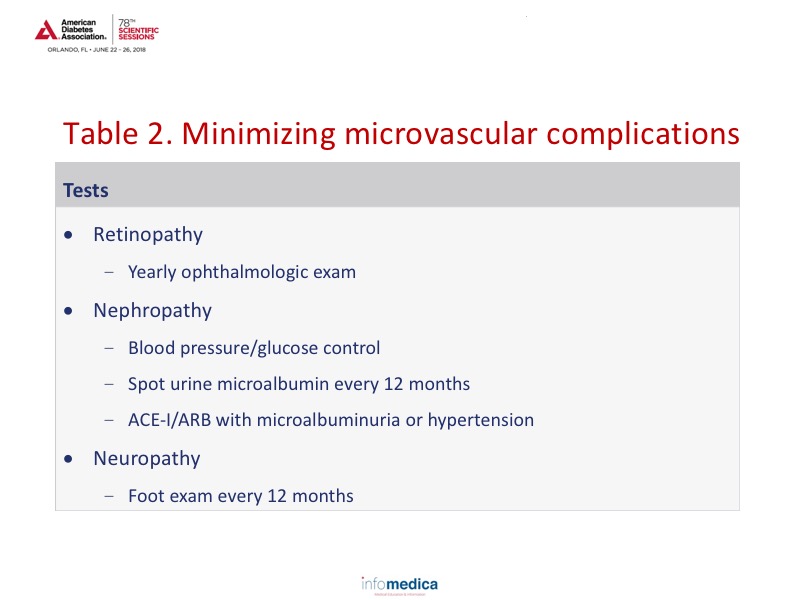

Nephropathy and neuropathy are commonly encountered in patients with HIV and may be unrelated to diabetes.22-23 Suggested recommendations for managing microvascular complications are provided in Table 2.

Key Messages

- HbA1c underestimates glycemia in HIV+ patients and may be a better option for diabetes diagnosis and management over fasting plasma glucose.

- ART may contribute to abnormal glucose metabolism.

- Treatment recommendations for diabetes in HIV+ patients should follow general guidelines.

- Attention should be paid to drug/drug interactions (dolutegravir/metformin).

- Diabetes is common in HIV-infected populations and has unique pathophysiologic and management considerations.

- Adequate control of diabetes and its related complications are essential for improving the health and lifespan of HIV-infected people.

REFERENCES

Present disclosure: The presenter has reported that no relationships exist relevant to the contents of this presentation.

Written by: Debbie Anderson, PhD

Reviewed by: Marco Gallo, MD